Defining Preventative Spend

Greg Notman, Harley Bryan and Amy Lloyd

December 2025

Introduction

Local Authorities across the UK are under increasing financial pressure. The Welsh Local Government Association (2024) estimated a budget gap of £559 million in 2025-26 for Council services in Wales. In response to these fiscal constraints, attention is returning to the role of ‘preventative spend’ in reducing future demand for services, including through efforts to address the factors that impact on our lifetime risk of ill-health. These social determinants – or ‘building blocks’ - of health include but are not limited to transport, employment, housing, education, clean air and safe surroundings.

Despite the increasing interest in preventative spend it is not always obvious which forms of spending are preventative. This makes it difficult to ‘protect’ preventative spend, and to assess return on investment from preventative activity.

This briefing note summarises the role of preventative spend, and some of the current approaches to defining preventative spend. It also provides practical examples of what might be considered preventative spend.

The role of preventative spend

Increases in acute demand and significant financial pressures, have led to Local Authorities cutting preventative spending (Hoddinott, Davies and Kim, 2024). In several policy areas, including health, homelessness and children’s services, there has been increased investment in short-term high-cost late intervention, and less focus on early intervention and prevention, which is largely attributed to rising demand for acute services (Scott, 2024).

Preventative spend interventions are cost-effective by reducing the need for more costly ‘acute’ services, or by improving individuals’ life-chances in a quantifiable way. For example:

- 63% of the public health interventions reviewed by NICE between 2011 and 2016 were cost effective, including 25% which were cost saving (Owen et al., 2017).

- Analysis of the Troubled Families Programme suggested it was cost-saving, with every £1 spent on the programme delivering £1.51 of fiscal benefit (Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, 2019).

- Pupils who had lived within 2.5km of a Sure Start children’s centre achieved GCSE results on average 0.8 grades higher than peers who lived further away and so had less or no exposure (Carneiro, Cattan and Ridpath, 2024).

However, these ‘savings’ are often realised over the longer term. In the case of the Sure Start Programme, it took years before benefits and savings were realised, and investment in the programme was massively reduced before causal links were drawn.

Savings achieved through preventative interventions may also accrue to other parts of the public sector (e.g. investment by a local authority may lead to reduced costs for the police or health boards).

So, while many interventions will have short-term impacts, preventative spend should be considered a long-term investment and monitored as such with thought given to how to account for any potential savings. However, the short-term nature of political cycles means decision makers frequently prioritise short-term results over long-term impacts, ‘overlooking the profound and lasting advantages of preventative activity’ (Scott, 2024: 9).

Tracking preventative spend in local government could help public bodies operate in line with the Well-being of Future Generations Act, with prevention and long-termism being two of the Act’s five ways of working. The Act places duties on public bodies to demonstrate their emphasis on prevention and how they are collaborating with others to do this (Howe, 2018).

However, it is difficult to track how much is spent on prevention, especially in comparison with previous years, as interventions are frequently not classified as preventative (O’Brien, Curtis and Charlesworth, 2023). Effectively tracking preventative spend requires a clear sense of what is defined as preventative.

Preventative spend in RCT

RCT HDRC are working together with the Council to develop a process that can enable the Council to map preventative spend and better understand potential outcomes.

To achieve this, we set out to:

- Define different types of prevention for a Local Authority context;

- Describe how much is being spent on preventative activities; and

- Assess the potential impact of spend in terms of outcomes for residents and communities and return on investment.

Defining prevention in a local authority context is difficult. We found that different service areas and individuals within them perceive prevention differently, making it challenging to make uniform judgements across service areas. Moreover, existing literature which aims to define prevention often does so with a focus on either national government or the health and social care system.

The Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy (CIPFA) and the Health Foundation have partnered with Local Authorities in England, as well as RCT to better understand the practices required to track and measure prevention spend, and the extent to which local authorities’ spending on preventative action can be quantified (Scott, 2025). We were able to collaborate with CIPFA, as well as the Office for the Future Generations Commissioner for Wales (FGC) to discuss and test definitions in practice.

Defining preventative spend

Preventative spend can be difficult to define and authors frequently use different criteria. We reviewed seven different articles to identify the key features of preventative spend (Wilkes, 2013; Craig, 2014; Cairney, St Denny and Matthews, 2016; O’Brien, Curtis and Charlesworth, 2023; Hoddinott, Davies and Kim, 2024; O’Brien and Charlesworth, 2024; Scott, 2025).

We found that preventative interventions typically align with the following four criteria:

- Clear connection to improving and sustaining determinants of health for individuals or communities;

- Intended to avoid or reduce negative outcomes;

- Intended to reduce demand on acute or statutory services; and

- A long-term multiple year investment

Spend can be classed as preventative, and then sub-categorised according to different typologies. Some use the term ‘non-preventative’ to describe activity designed to support basic operations or reactive services that have minimal impact on future demand for reactive services. We do not use a non-preventative category for our tracking of spend as our analysis focuses on the proportion of total spend considered to be preventative.

CIPFA also employ an ‘enabling’ category, for spend or activity which is not preventative in itself but is required to support or facilitate the delivery of a preventative activity (Scott, 2025). We have also not employed this enabling category in our work in RCT to date.

Forms of preventative spend

There are four different forms of preventative spend: foundational, primary, secondary and tertiary. Extant literature highlights that it can be difficult to categorise interventions, as boundaries often become blurred. However, Scott (2025), identifies the importance of two factors in helping categorise preventative spend:

- Primary purpose: who the activity is aimed at; and

- Target population: who the activity is aimed at.

We found that focusing on the primary purpose and target population to be particularly effective in categorising local government spend and achieving consensus between different groups.

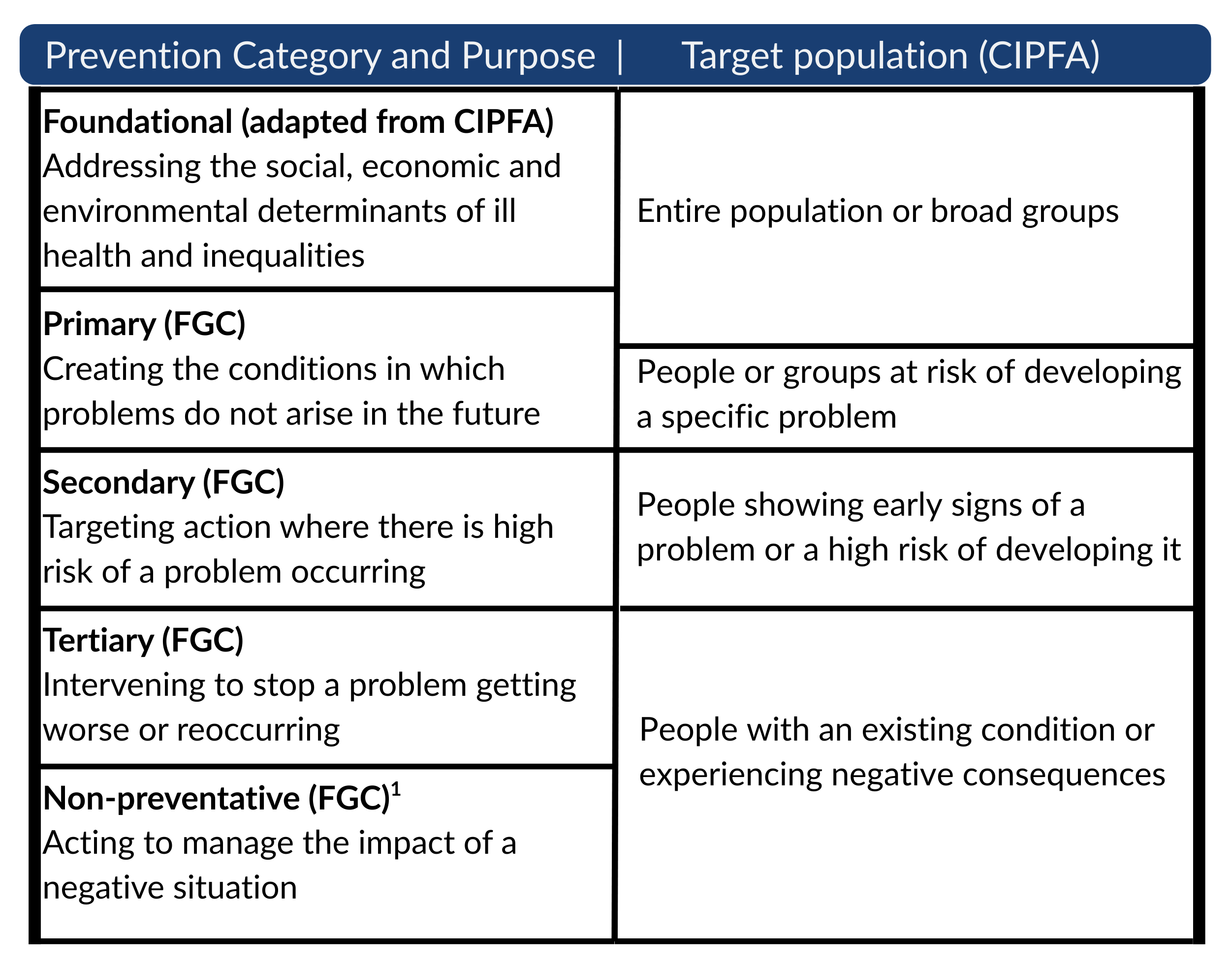

The table below describes each of these forms of preventative spend.

Foundational prevention also known as primordial prevention, aims to address the social, economic and environmental determinants of ill health and inequalities. This can involve supporting infrastructure enables people to live healthy lives and (O’Brien and Charlesworth, 2024). These interventions are typically targeted at the entire population, or broad groups. Some definitions of foundational prevention only discuss social capital, and treat economic prevention separately; our definition encompasses the infrastructure required to address the social, economic and environmental determinants of health.

Some categorisations of prevention encompass this within primary prevention, but local authority officers highlighted the importance of this for their work.

Primary prevention aims to create conditions where problems do not arise in the first place (Local Government Association, 2017; Hoddinott, Davies and Kim, 2024). This may involve early intervention to reduce future demand on acute services (Cairney, St Denny and Matthews, 2016). These initiatives tend to be targeted at the entire population, or at broad groups, including those at risk of developing a specific problem.

Secondary prevention is more targeted intervention where there is a high risk of a problem occurring. This may involve detecting and mitigating the early stages of a problem, to stop it developing into a severe case (Local Government Association, 2017; Hoddinott, Davies and Kim, 2024). Interventions are targeted at those showing early signs of a problem, or those with a high risk of developing it.

Tertiary prevention typically is aimed at those with an existing condition or experiencing negative consequences. Intervention aims to stop a problem getting worse or reoccurring, and may seek to reduce, manage or mitigate the impact (Hoddinott, Davies and Kim, 2024; Scott, 2024). This may occur alongside or after involvement with acute services.

1 We do not cover acute or non-preventative spend in our analysis and instead look at the proportion of total spend which is preventative.

References

Cairney, P., St Denny, E., and Matthews, P. (2016). Preventative spend: public services and governance. University of Stirling. Retrieved from https://dspace.stir.ac.uk/handle/1893/25968 (external link)

Carneiro, P., Cattan, S., and Ridpath, N. (2024). The short- and medium-term impacts of Sure Start on educational outcomes. Institute for Fiscal Studies. IFS Report R307. Retrieved from https://ifs.org.uk/publications/short-and-medium-term-impacts-sure-start-educational-outcomes (external link)

Craig, N. (2014). Best preventative investments for Scotland – what the evidence and experts say. NHS Health Scotland. Retrieved from https://www.scotphn.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/24575-Best_Preventative_Investments_For_Scotland_-_What_The_Evidence_And_Experts_Say_Dec_20141.pdf (external link)

Hoddinott, D., Davies, N., and Kim, D. (2024). Fixing public services: local government. Institute for Government. Retrieved from https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/fixing-public-services-labour-government/local-government (external link)

Howe, S. (2018). Tough times call for bold decisions on preventative spend. Future Generations Commissioner for Wales. Retrieved from https://www.futuregenerations.wales/news/tough-times-call-for-bold-decisions-on-preventative-spend/ (external link)

Local Government Association (2017). Must knows for elected members: prevention. Retrieved from: https://www.local.gov.uk/publications/must-knows-elected-members-prevention (external link)

Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. (2019). National Evaluation of the Troubled Families Programme 2015-2020. Family Outcomes – national and local datasets, Part 4. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-evaluation-of-the-troubled-families-programme-2015-to-2020-findings (external link)

O’Brien, A., and Charlesworth, A. (2024). Counting what matters: How to classify, account and track spending for prevention. Demos. Retrieved from: https://demos.co.uk/research/counting-what-matters-how-to-classify-account-and-track-spending-for-prevention/ (external link)

O’Brien, A., Curtis, P., and Charlesworth, A. (2023). Revenue, Capital, Prevention: A new public spending framework for the future. Demos. Retrieved from https://demos.co.uk/research/revenue-capital-prevention-a-new-public-spending-framework-for-the-future/ (external link)

Owen, L., Pennington, B., Fischer, A., Jeong, K. (2017). The cost-effectiveness of public health interventions examined by NICE from 2011to 2016. Journal of Public Health, 40(3), pp.557-566.

Scott, Z. (2024). Exploring levels of preventative investment in local government in England. CIPFA. Retrieved from https://www.cipfa.org/services/integrating-care/investing-in-prevention (external link)

Scott, Z. (2025). Understanding preventative investment: a practical approach to map and measure spend. CIPFA. Retrieved from: https://www.cipfa.org/services/integrating-care/investing-in-prevention (external link)

Wilkes, L. (2013). Tracking your preventative spend: a step-by-step guide. Local Government Information Unit. Retrieved from https://lgiu.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Tracking-your-preventative-spend.pdf (external link)

Welsh Local Government Association. (2024). Council Services face “unsustainable” budget pressures. Retrieved from: https://www.wlga.wales/council-services-face-%E2%80%9Cunsustainable%E2%80%9D-budget-pressures-says-wlga (external link)